Editor’s Note: In 1996, the Canyon Echo published a four-part series entitled “Life along the San Juan River” for the Utah state centennial celebration. The series was part of the Bluff Legacy Project and was made possible with support from the San Juan County Historical Commission. More acknowledgements from the original article are included at the end of the piece.

By Phil Hall

In writing this last of four articles about life along the San Juan River, I talked to some of the oldtimers who still remember crossing Comb Ridge before paved roads. This is not history. It is more important than that. It is folklore. It is the way things were in the minds of people who still remember them. It is based primarily on oral interviews and writings from a few men who lived during that era.

There was a time before there is now. It was a time very different from our own. It was a time of vastness, known only by the people who lived it. It was a time of incredible difficulties, dark places and rough roads.

Though most of us did not live in that time, we can, perhaps, grasp its significance, its brilliance, and the rough texture of its surface. We celebrate the times gone by in a place called the Utah Strip.

There is a narrow strip of land in southern Utah which stretches from east to west, from the Colorado border to Navajo Mountain. It is roughly bounded on the north by the San Juan River, and on the south by the Arizona state line. It is the frontier where American expansion ran aground in the muddy waters of the San Juan River. It is the northern edge of the Navajo Nation, whose boundaries have shifted as readily, and almost as often, as the sands of the river itself, since its establishment by the Treaty of 1868.

Referring to the area both north and south of the river as the Utah Strip gives one a geographical grasp of an otherwise elusive landscape. The river divides and unites the country through which it passes and gives it shape, providing an obstacle to north-south travel while providing a means of westward transportation.

The Utah Strip is rich in the legends and folklore of modern-day Hopi, Zuni, Acoma, and, indeed, all of the Pueblo peoples who have come to know this country from prehistoric times to the present.

It is populated by Anglos and Navajos today, but once it was occupied by Utes and Paiutes as well, and by farmers, miners, ranchers, boaters, explorers, and adventurers, lured by the swift-moving waters for a chance to hunt or trade, mine or farm. It has provided opportunity for some, and disaster for many more, as the river knows no whims but her own, answers no calls except to the dynamism and power of her own resurgent self. The central feature of the Utah Strip is the San Juan River, and the geologic magic which only she weaves.

If there is one characteristic of the Utah Strip which persists in this century, it is the struggle for the land: for the use of the land, possession of it and extraction of resources from it. Struggle for possession of lands north and south of the San Juan River continued well into the 20th Century, and to some extent continues today. But it was an agreement signed into effect in 1933 which ceded the Navajo Nation expansion northward from Monument Valley to Mexican Hat in the west, and created the Aneth Extension in the east.

Exploration for mineral resources began even before the new century dawned. Swarms of rough hewn men descended on the banks of the San Juan with their tools and mules, in search of rich paydirt, the flour gold that would make men rich overnight. Men were slain by by Utes, Paiutes and Navajos while trying to find silver in Monument Valley and on Navajo Mountain. Some found copper, some found oil, and later, uranium. Before the first Mormon pioneers reached this country men were prowling the banks of the San Juan looking for gold.

Mineral extraction has been a way of life since the first white men arrived on the Utah Strip, and it was mineral extraction which brought roads into previously roadless areas, electricity to dark places, jobs to people who wanted them. Gold, silver, copper, oil, gas, uranium, and gravel have all been mined here. These various boom and bust cycles have brought men to San Juan County who wanted to make their living while they could, for making a living in this poor country has always been, for most, a difficult thing to do. Some of those men stayed and raised families, and continue to live here today.

A historically significant institution all around the Navajo Nation was the trading post, which has quietly disappeared, along with the traders themselves, replaced by the gas and convenience store. The disappearance of the trading post marks a significant change in the culture of Navajo people and in the relations between Navajos and Anglos.

Traders generally spoke the language of the Native Americans with whom they traded, knew the families in the area, provided a social center, negotiated disputes, and served as an information center in isolated areas. But more than anything else the trading post provided a sound economic basis for the sustenance of Navajos and Anglos alike. It was a symbiotic relationship, one steeped in the Navajo culture for hundreds of years of trading with Pueblos, Spaniards, and Mexicans.

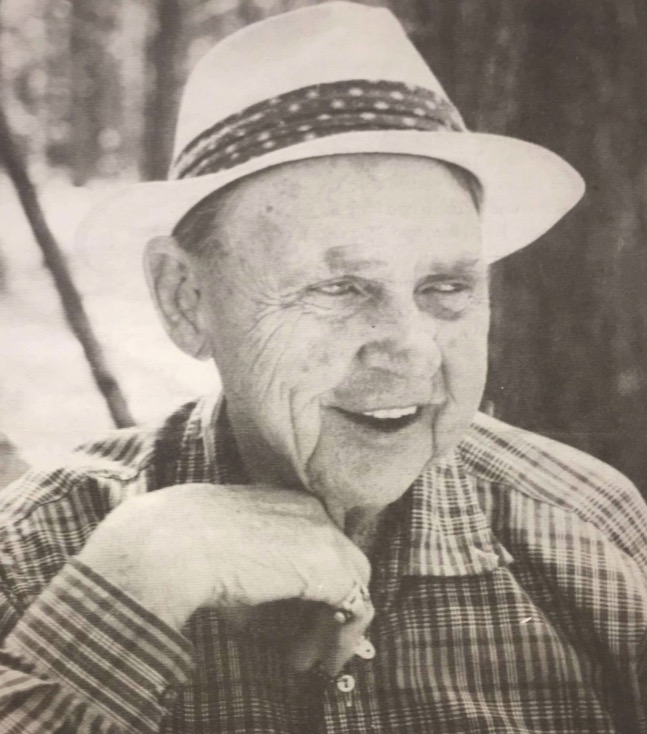

Ray Hunt, who currently lives in Blanding, Utah, goes back further than any other trader still extant, and knows more about trading with the Navajo than anyone else alive. He is also a man who has worked from Aneth to Oljato, trading, driving trucks, herding sheep, buying and selling goods, and like everyone else in San Juan, doing whatever he could to make a living for his family.

Hasteen Beghani, as the Navajos called him, lived through four major wars in the 20th century. Born in 1902, Hunt saw an influenza epidemic wipe out half of the Navajo population in 1918, a typhoid epidemic, the last Ute uprising, Prohibition, the Great Depression, the coming of electricity, the oil and uranium booms, and the end of the trading post as a way of life on the Navajo Nation.

Hunt moved to Aneth in 1917 and to Bluff in 1920. Throughout his long career as a trader, he traded in Chilchinbito, Teec Nos Pos, Oljato, Mexican Hat and Monument Valley. He traded with the Navajos from one end of the Utah Strip to the other.

“We got the Aneth Trading Post from Tom Dustin in about 1917,” Hunt said, “and we were there until about 1920. We had a big hay farm there, and the government farmer, Herbert Redshaw, lived just under the hill from us.”

Hunt traded with the Navajos during World War I and he learned to speak their language when he was just a kid.

“We’d been on the Reservation years before we came to Aneth. We were in Teec Nos Pos first, and then Mexican Water. From Mexican Water we came to Aneth. Then from Aneth we came to Bluff in 1920.”

The Navajo brought lambs into the trading post in the fall, and their wool in the spring. They brought in Navajo rugs and hides and silver jewelry to sell. “Back in that time there weren’t too many automobiles around. It was all horseback and wagons,” Hunt said.

Wool, sheep and hides were sold by the trading post to the wholesale houses in Fruitland, New Mexico. Silver jewelry was a common commodity among the Navajo in the early part of this century, but was probably here long before that.

“I think they (Navajos) have made jewelry since the Spaniards introduced it to the Navajo people. I think they started hammering out a little silver. A lot of them used American money to make it. They also used silver coins or Mexican money, Mexican pesos.

“Of course, they would pawn it (jewelry). The only source of credit they had was their pawn. The traders would take their pawn and hold it for six months. When they would go to sell their wool in the spring they would redeem their pawn, and then when they sold their lambs in the fall they would redeem their pawn.”

The reservation traders didn’t own their trading posts. All they owned were their licenses. Some of them had short-term renewable licenses, and some of them had longer-term licenses. Ray Hunt had 25-year licenses all of his trading life.

“I built a new store after we went to Chilchinbito, and that became the property of the Navajo Tribe. They still rent it out to traders, but it still belongs to the Navajo Tribe when the traders leave. So the reason for getting longer leases was because later along in years if you ran a trading post you couldn’t afford to put in all the requirements that they (Navajo Tribe) wanted without a longer lease. If you had a 25-year lease you could afford to put in your walk-in ice boxes and refrigeration.”

Hunt remembers the flu epidemic which occurred in 1918. It hit especially hard on the Navajo and Ute reservations. “Sometimes you would only find one person out of their whole family that was alive. I don’t have any idea how many people they lost, but I imagine they lost half of their population.”

The 1920s brought Prohibition, when imprisonment was the penalty for making bootleg liquor. “There was an awful lot of bootlegging going on along from 1920 up to 1928,” Hunt said. “A lot of bootlegging around this whole area. That’s about the only honest thing they had left.

“The government tried awful hard to stop bootlegging, and it cost the government lots and lots of money. But often in these areas where it was hard to get to, where there were no roads, that’s where bootleggers hung out. That’s where your moonshiners were.”

The “Prohis” as they were called, weren’t locals, they were from out of state, government prohibitionists. Ray Hunt remembers a Prohibition story:

Prohis: Where is your father?

Kids: He’s up in the canyon.

Prohis: What’s he doing?

Kids: Well, he’s running off some whiskey.

Prohis: How far is it up there?

Kids: It’s about four miles.

Prohis: Well, I wonder if we could get a horse from you to ride up there?

Kids: Sure, but it will day cost you five dollars for the horse.

Prohis: We will pay you when we get back.

Kids: No, pay me now, because if you go up in that canyon you won’t be coming back.

The Great Depression was a hardscrabble time for everyone. Hunt remembers that time down on the Navajo Nation: “The Navajos survived it better than the whites, because they were living off the land, and there wasn’t near the population (of Navajos) then as there is now. That was before the stock reduction, and they had a lot of sheep and cattle and fruits.”

It may have been the federal government stock reduction program which hit the Navajo people hardest during the Depression. It was a program started in the 1930s, designed to reduce overgrazing. “When I first went to Mexican Hat it was the start of the stock reduction,” Hunt recalls. “The government came in and said that the Navajos had to reduce the number of stock they were grazing on the reservation. Said they were overgrazing the reservation. Then, if they couldn’t sell their stock, they would just drive them into a canyon and shoot them all. I think it was a bad thing to have done. A lot of the Navajos went to jail rather than give up their stock. They bucked it. But they were forced to do it. If the Navajos wouldn’t obey the law they put them in jail down at Tuba City and took their stock anyway. That’s about the time I left Gouldings and started my own trading post at Mexican Hat.”

The government stock reduction program continued until 1945. Even today Navajos will tell you that their stock is part of their culture. The land possessed on the present-day reservation is not owned outright. They have grazing rights granted through the Navajo Nation, and building site leases. Their grazing rights give them rights to the land. If they lose their grazing rights, they lose their attachment to the land. To the Navajo it is part of their culture, part of their way of life. Even today, very old Navajo women keep their flocks of goats and sheep. In the rugged country of Navajo Mountain you can still see a traditional elderly woman herding her flock on a horse through the sagebrush. Leonard Lee, Aneth Chapter President, recently told us that his 99-year-old grandmother still keeps her flock.

Many Navajos resisted stock reduction until the end. In the fall of 1944 Ray Hunt bought another trading post in Chilchinbito. “I think all of the traders hated to see stock reduction happen. The Navajos never fully recovered from it. They just couldn’t understand why it had to happen.”

Ray Hunt was down in Oljato and Monument Valley during the Great Depression. He still remembers the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) projects of that time.

“I was working for Gouldings Bob Howell, stand down in Monument Valley,” Hunt said. They had CCC camps down there where they were building mostly reservoirs and developing springs and doing that type of work.

“The stores, Oljato Trading Post and Gouldings, would give the Navajos credit for groceries, and hay and grain for their horses. That’s the part where I came in. I’d go out to the camp when they paid off and I’d collect my bills and the other trading post would also be there to collect his bills.

“They had about 150 or 200 Indians working for the CCC. They were desperately in need of work in those days. They all had families to feed. All of the Monument Valley Indians built corrals, stock water tanks, whatever was needed in the community.”

During World War II enlistees from both sides of the frontier enlisted or were drafted into service in the military. The Navajos were sent to the Pacific Theatre where they were used as radiomen. They were the famous Navajo Code Talkers who developed a code the Japanese never broke, and which may have been a deciding factor in the U.S. victory over Japan in the Pacific. After the war a new wave of immigrants came to the shores of the San Juan.

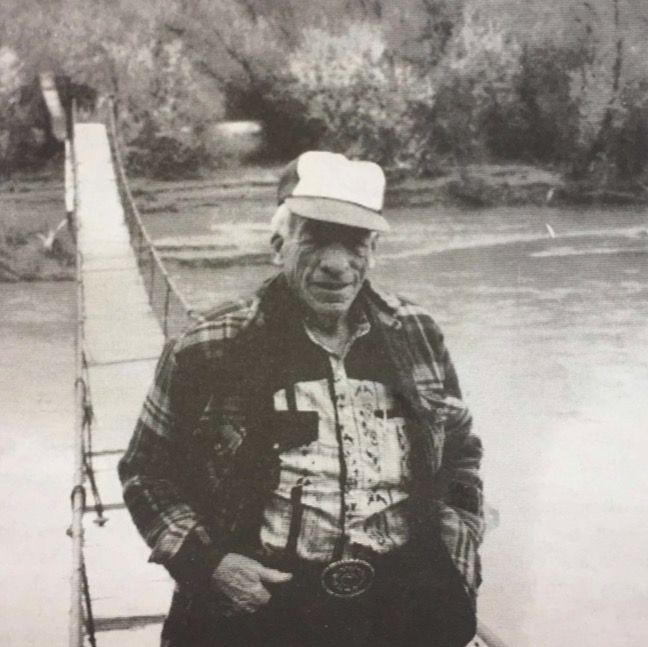

Bob Howell is from a later generation than Ray Hunt. He still lives in Bluff, where after serving in the European Theatre in World War II, he returned to farming east of Monticello, at a place called Summit Point. He tried to grow wheat, but “I mostly raised dust,” he said. When asked if it was dryland farming, he said, “Very dry.”

He came to Bluff in 1956 to visit relatives and never left. He tried farming, but soon saw that he couldn’t make a living farming. Howell worked hauling freight across the Navajo Nation, peddling produce, hauling milk, hauling some ore. “Just about anything you could do to make beans,” he said.

Howell is regarded as one of the best gardeners in Bluff today. He raises hollyhocks, in their many colors, which tourists marvel to see. A tourist asked him one time why he raised hollyhocks. “Just for the hell of it,” he said, smiling across the fence. All of the newcomers on Howell’s side of town come by to get gardening advice. He will always lean across the fence and talk gardening with you in a quiet, modest way.

There weren’t any bridges between Bluff and Mexican Hat in the early 1950s. A person driving between those two towns had to cross the washes, and if the washes were flashing, a person had to ford them or wait until the water subsided. Trucking from Bluff to Mexican Hat before paved roads or bridges was a harrowing experience, not the least difficult of which was crossing Comb Ridge. Howell worked hauling ore from the Happy Jack Mine on Cedar Mesa to the mill in Halchita. It was because of the mill that electricity came to Bluff in the late 1950s. It was the uranium boom that caused the road up the Mokee Dugway to be built. From the 1950s into 1960s the uranium boom continued unabated throughout the Colorado Plateau region. One Navajo spokeswoman stated that there are, even today, more than 1,100 abandoned open uranium mines on the Navajo Nation. Bob Howell stayed busy hauling ore and yellowcake.

Because of seeps discovered along the San Juan River in the area of Mexican Hat, the exploration for oil occurred in Mexican Hat just after the turn of the century, much earlier than it did on the Aneth Extension. It was a poor oil patch and never did amount to more than a bare subsistence venture, and even today produces small amounts of oil.

Dick Wing has recorded some of his recollections, growing up as a youngster in Mexican Hat, where his father spent years trying to make a living in the oil business. “He (George Wing) drilled, he pumped, he cursed, he kicked and eventually made a little money from his beloved enterprise,” Dick Wing recounts.

George Wing had a “lifelong love affair with the blowing sands, poor roads, no electricity, scarce housing, bad water, intense heat, and the most beautiful scenery in America that was the San Juan,” Dick Wing says.

“Dad hauled his crude oil to Salt Lake in an old beat-up tanker and brought back refined gas that he sold to stations in Monticello and Blanding. He kept a little to sell from a glass-topped pump my brother and I manned in Mexican Hat.”

Bob Howell arrived on the Utah Strip just in time to witness the Aneth oil boom on the east end of the Utah Strip. “You could look down from the top of McCracken Mesa and it was just a city of oil derricks,” he said. The Aneth Oil Field is much larger than anything else discovered in the Four Corners region. Estimated at 100 million barrels in the 1950s, it has produced 488 million barrels of oil to date and has provided a significant economic boon for the Navajo Nation, San Juan County, and the State of Utah.

Men from Bluff working in the oil fields south of the river left trucks and materials on the other side and traveled to Mexican Hat, where they crossed the San Juan River and then traveled reservation roads east to the oil fields. It sometimes took three hours to get to work.

Swinging bridges were built across the river at Bluff and Montezuma Creek. Men carried tools, supplies, gas and oil across the swinging bridges onto the reservation. The construction of the swinging bridges had another, unexpected benefit. The Navajos have used the swinging bridges for years to cross the river. The swinging bridge east of Bluff provided Navajos living in the Casa del Eco area foot access to the Mission and to Bluff.

The swinging bridge became part of the culture of the area, and continues to be so even today, although the emphasis has changed. Today the Bluff bridge has fallen into disrepair, and although both San Juan County and the Bureau of Land Management deny ownership or responsibility for it, the swinging bridge continues to be a tourist attraction for people who want to visit 16 House Ruins on the Navajo Nation.

Many things about life on the Utah Strip changed as a result of the oil and uranium booms. Paved roads and electricity were two big ones. It would be difficult to imagine a place more isolated before those two elements arrived on the Utah Strip. Imagine a great sea of darkness where a mere trip to civilization for basic necessities was an invitation to adventure and disaster. Imagine crossing Comb Ridge with a load of ore in an old sprung flathead truck when the roadbed itself was nothing more than rock, a great deal of it loose. It took a half day to get to Mexican Hat, a day to get to Monument Valley. Before the highway bridges were built across the river at Montezuma Creek and Bluff, the bridges at Four Corners and Mexican Hat were the only way to cross the river. Travelers from southwestern Colorado during the 1930s and ’40s traveled to Monument Valley by way of Kayenta, and for many years those roads were dirt.

Ray Hunt broke an axle in his old Ford car one time in Oljato. He walked and hitched back to Douglas Mesa where his flock of sheep and goats were, and then drove the flock on foot the twenty-odd miles to Mexican Hat. From Mexican Hat he herded them onto Bluff, where he found an old Ford, wrecked, with a good axle in it. He borrowed some tools, extracted the axle from that old Ford, hitched a ride back to Oljato, installed the axle in his car, and drove to Bluff.

Many vehicles crossing Comb Ridge with a load had to back up over the ridge in order to keep their gas supplies higher than their engines , in the days before modern fuel pumps; another neck-breaking event. It’s a wonder there’s anyone alive in this whole country.

Adolph Coors III had an experimental farm near Center, Colorado, when Roy Pearson arrived there shortly after World War II. After service in Germany during the war, Roy Pearson got a job on that Coors farm, taking care of the Black Angus cattle raised there. One of the principal crops was Moravian Barley. Coors discovered that Moravian Barley raised at those high altitudes produced a barley with a higher sugar content. Coors and Pearson got to be friends, but after Coors was murdered mysteriously, Pearson came to Utah.

He worked at the uranium mill in Monticello until the one started at Halchita, across the river from Mexican Hat, then Pearson came down to Bluff. He also hauled ore from the mines at Little Mae, Bull’s Eye, and Happy Jack across Cedar Mesa, down the Mokee Dugway, to the Halchita mill, where yellowcake was made.

Housing was nonexistent. People lived in tents and slept on the ground. “It wasn’t possible to haul a trailer in there from Bluff,” Pearson said. “You couldn’t get one across the washes. It would high center and you would tear it apart. But somebody managed to get one in there from the Monument Valley side and I bought it. Pretty soon I had seven guys living in that trailer house.”

When Pearson first came to Bluff in 1955 there were no paved roads around Bluff, nor any electricity, either. “The road to Blanding was just a trail in those days,” he said.

Likewise for all of the roads going out to the oil rigs on the reservation. Most of the men who worked on the oil rigs commuted from Cortez, Colorado, but some commuted from Bluff.

The uranium, gold, silver, and copper have long since faded away. There is a new form of industry on the Utah Strip called tourism. Today, tourists from all over the world pass through the Utah Strip, from Monument Valley through Mexican Hat and Bluff, and on to the ruins at Mesa Verde and Durango in southwestern Colorado. They come because they want to witness the spectacular scenery and the Navajo culture. Most of the roads north of the river are paved now and, except for the Navajo Nation, there is electricity everywhere.

The times have changed, and with the changes a new and different breed of people have come to live on the Anglo side of the San Juan. They aren’t farmers or ranchers, miners or oilmen. They are more likely to be environmentally conscious, more likely to own computers than plows. They have more formal education, and most of them are emigrants from another place, drawn to southern Utah by the quiet, rural lifestyle and grand vistas.

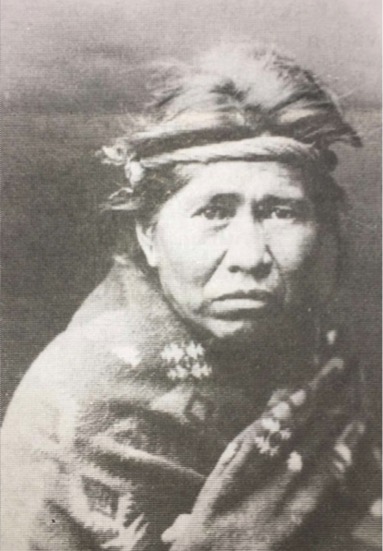

The Navajos drive pickup trucks instead of horses but the roads south of the San Juan River are still largely dirt. The Navajo artists and crafstmen (and women) still produce some of the finest work to be found anywhere in the United States, but rarely work in the uranium mines. The Navajo women weave blankets and baskets of incomparable quality, and the men work silver. Many times whole families leave the reservation to find work. Trading posts don’t trade for wool and sheep anymore: they trade for cash.

A little oil is pumped out of the ground at Mexican Hat, and the Aneth Oil Fields are still big producers, although their production is considerably less than it once was. The gold and silver booms died almost before they got started, and there is little demand for uranium resources. Twelve thousand recreationists float the San Juan River each year. Many thousands more hike the canyons in search of Anasazi ruins and quiet skies.

It is still the desert. It is still a place where you can die if you go out unprepared, but it it is different than it was sixty or seventy years ago. It is not as risky as it once was. And as more people come here from other places they will try to make it safe for themselves.

Despite the changes, however, this place we call the Utah Strip is still a place of quiet, a place of mystery, a place of mixed cultures, a place we call home.

— Phil Hall, author of “Crossing Comb Ridge”, is was editor of the Canyon Echo from 1993 to 1997.

— Thanks to Janet Wilcox, LaVern Tate, and the San Juan Historical Commission for the Ray Hunt interview and for loaning some of their historical photographs to us for this last edition of the Bluff Legacy Project. We would also like to thank Anne Egger, Ellen Meloy, Jackie Warren, and Beth King for their editorial help.

— A special tribute should be paid here to Dr. Robert McPherson for his wonderful book, A History of San Juan County, which has provided both information and inspiration for this present work.

— A very special thanks to authors Terri Winder, Doug Ross, and Beth King for their contributions, and Linda Richmond for the many sleepless nights she put into editing, proofing, and typesetting. And, finally, thanks to the Utah Centennial Commission and the Utah Humanities Council for believing in the worth of this project.

— This article was first published by the Canyon Echo in December 1996 and is reproduced here with permission from the publisher.